Last year, for several days, the world has been anxiously watching the election of the US President. In the US, of course, it has been the topic of the year, for some even more important than the pandemic. As with every election, political commentators, opinion polls, political scientists and so on have been supplying a lot of information. However, after the successes in predicting Trump’s victory four years ago in the so-called prediction markets, it is the prediction markets that the public has been looking more deeply at, at least in the last few days of the election. In this article, I will not focus on the US President, but on just how we can use prediction markets to gather information and make better decisions. And not just in politics.

What the prediction market looks like

A prediction market is simply a bet with a market price. Let’s take a look at Catnip Exchange, which is the front-end to the Augur crypto prediction market with an integrated automatic market maker (AMM) called Balancer:

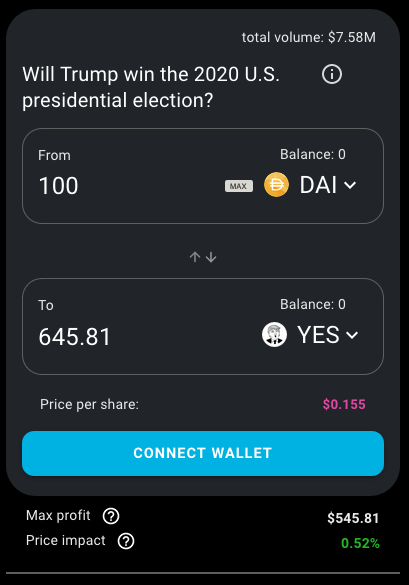

This interface gives us access to the ability to trade between dollar value (represented by the dollar-linked cryptocurrency DAI) and winning tickets. The “YES” ticket is easy to decipher by the icon – if you have one “YES” ticket (or yTrump), if Donald Trump wins, it will pay you one dollar. A “NO” ticket – nTrump (with a picture of a crossed out Trump) will pay one dollar if Donald Trump doesn’t win.

We can see that 100 DAI (“dollars”) can buy up to 645.81 YES tickets. If Donald Trump had won, we would have earned (in addition to our initial investment) $545.81. If Donald Trump loses, the tokens are worthless and will simply be forfeited (and we have lost a hundred dollars).

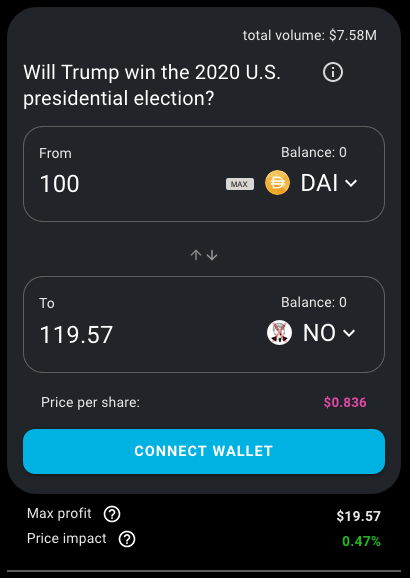

The NO ticket has a higher market price, for 100 DAI we can buy just under 120 tickets.

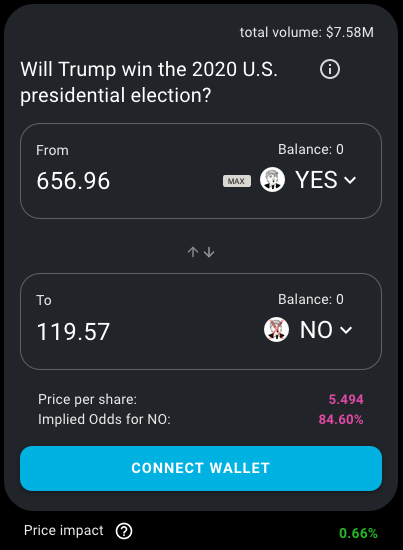

We can also trade tickets for each other:

From the ratio of their prices, the exchange will also calculate the probability that the “NO” ticket will be the winning ticket, in this case, at the time of writing, the probability that Trump will lose according to the market price in the prediction market is 84.60%.

As these tickets are tradable all the time, their market price varies. Thus, new information is always coming into the forecast. If someone has some information that changes the probabilities, they can trade that information. They do not have to bet on the final outcome, they can bet on current odds.

Let’s imagine the unlikely scenario that Trump has an ace up his sleeve – for example, he found a way to declare the election invalid or something similar. Anyone with this information knows that the price of a YES ticket is too low – the actual probability might be 40%, for example, but the market says 15.4% (=100%-84.60%). Thus, a person with this information may not think the probability of Trump winning is higher than 50%, but it is higher than it is now. He can buy Trump’s YES tokens before this information becomes public. And 24 hours later, he can sell them at a price of $0.4 per token – because the perceived probability has changed.

The prediction market thus incentivizes all those with better information than the current market price provides to trade this information. Thus, by individual trades we make the information more precise.

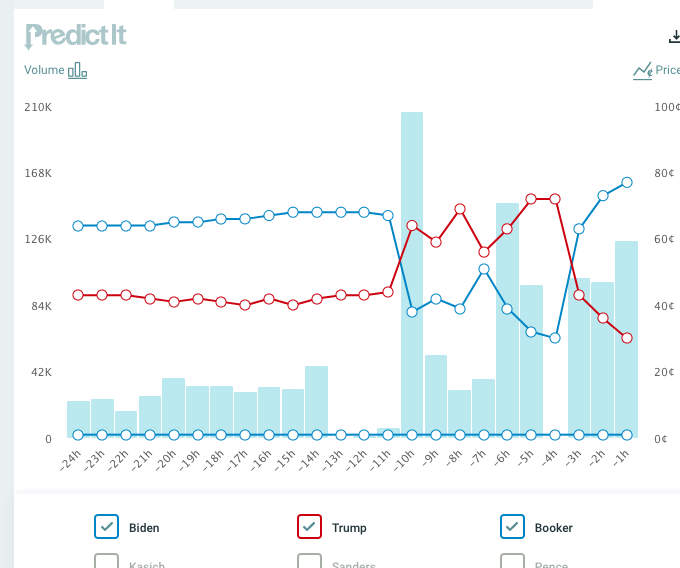

Tomas Forgáč noted that while the media was still reporting Trump’s lead, the prediction markets flipped the market price, about three hours before the information was “public.” Of course, what is public is relative; even in the age of the Internet, information spreads at some speed – journalists have to process it, write it, etc. But even “flash reporting” of news has not been as fast as the market price – although various analyses have discussed this possibility. The question is always – what analysis are we going to believe?

Arbitration

And here comes another nice feature of prediction markets. If the odds in two markets are different, another market player comes in and does what is called arbitrage. In arbitrage, the arbitrageur has no extra information. If a YES ticket is priced at $0.2 in one market and $0.4 in the other, by simple market operations he can buy the YES ticket in the cheaper market and sell (short) it in the more expensive market. In that case, he immediately earns $0.2 per ticket – regardless of the outcome. Of course, the execution of this operation has various limitations, for example, a YES ticket in the crypto prediction market is indeed represented as a “cryptocurrency”, but this does not mean that you can send it to a traditional bookmaker and sell it, so you need to compose your bets in such a way that this market actor is neutral to the outcome, but earns a profit on the difference in price. The specific approach depends on the markets.

Unlike market actors who supply information, arbitrageurs equalize prices. Thus, prices in different prediction markets are very similar (they may differ only by the transaction costs of conducting the arbitrage).

If we have hundreds of different pollsters, a CNN commentator, a Fox News commentator, a blogger, members of election staffs, foreign media commentators, and so on, everyone has their own opinion, their own analysis, or their own results that they present.

Which of them is right?

There is no arbitrage between the opinions of a CNN commentator and Fox News. They are separate islands with different audience bases. Information flows both ways, but polarized media rarely find consensus.

The prediction market converges to a single probability distribution thanks to arbitrageurs. So it doesn’t matter if the prediction market is “red or blue”, the market is not trading “I would like” but “I think it will happen”. And every opinion about what will happen is backed by a financial investment.

Journalists and experts may lose their reputation, but it rarely has a long-term effect for them. My favorite example is Paul Krugman, who has a “Nobel Prize in Economics” but his predictions are usually so off that some people trade the “inverse Krugman” strategy – I’m betting that exactly what Krugman says won’t happen. Despite that, he is still considered an expert. We have countless similar experts in cryptocurrencies.

The mechanism of how we find these experts is also interesting. In most cases, the amount of successful experts is determined by their entry into the funnel rather than their skills. If we have 100 chimps at the entrance to the funnel who can buy YES and NO tokens by hitting the red or blue button, at the end of the election we have an average of 50 experts whose predictions worked out. If we repeat this six times, out of 100 “experts” we have on average three who were not wrong. But if we start with a million experts, after five elections we have 31250 experts who randomly “predicted” the future.

The problem is that banging on buttons has almost no cost. So an expert’s career is based on setting up a Twitter account and subtle marketing about what correct predictions one has. Even a few incorrect predictions are easy to talk down and thus people like Krugman still have a chance to make predictions. Paradoxically, then, it’s more interesting whether their prediction produces a clickbait article, and more valuable the amount of predictions that can be made into long articles for which the journalist is paid by character count, than their reliability.

The market solves this problem by “fact checking” in the form of a profit and loss statement. Of course, a successful information trader can also get lucky, and the math works the same way for him – except that every prediction has a cost (prediction means investment in the prediction market). Of course, the returns are somewhere else entirely too – instead of an expert coming to do a paid talk at some business conference in an airport hotel, they make quite a bit of money. If they’re right.

Insiders – not everyone’s opinion is interesting

I’m all for letting everyone speak their mind – and for not having to listen to them. On this topic, it’s great to read the book “Skin in the game” by Nassim Nicholas Taleb.

I remember talking to journalists who were publicly commenting on the price of Bitcoin. “It’s a bubble” and the like. I always ask how big a short position they have open. If none, I say – OK, they have an opinion, maybe they don’t know how to short. So I suggest a bet. I phrased it simply: “we’ll put a private key to bitcoins worth $100 and $100 banknote in a sealed envelope. Three years from now, we open the envelope, and whoever’s choice is worth more gets both and a dinner invitation from the other party, who will have to listen for two hours of the winner’s bragging.” The journalist, of course, refused. Opinion in a newspaper is something they get paid for. But standing by their prediction (which incidentally is perhaps the basis on which some of the more foolish readers make market decisions) is not what they do to get paid. This is an exact example of the absence of skin in the game – if a journalist wrote anything at all about Bitcoin, he would get paid for the words.

By the way, one of those bets I suggested I would probably lose :). So I’m glad I didn’t have to listen to the journalist in question to brag about how right he was.

The advantage of prediction markets is that not everyone’s opinion matters equally. There are plenty of Biden or Trump supporters who are going to bet $10 or $100 on their favorite. But if someone has truly credible information, it’s worth betting orders of magnitude more – and that’s regardless of the final outcome, which is largely stochastic. If a pollster asks a representative sample of 10,000 voters, they have no incentive to answer truthfully. They can change their minds. Moreover, with such a large number of voters, it is very difficult to select a representative sample; the margin of error is huge – usually higher than the signal. If the poll is a telephone poll, it is possible that Trump voters are neurotic and will just hang up. Or Biden has more voters among Gen Z, which don’t answer calls from unknown numbers. If it’s a door-to-door poll, the father of the family might not want to admit to the kids that he’s going to vote for Trump, so he’ll say “I don’t know yet” or “Biden.”

Of course, all of these biases in the data are addressed by survey firms with various model-based corrections. The question is whether this is achievable.

If I know the probabilities better than anyone else, the cost of the survey can be recouped the next time I make a good trade.

Using prediction markets in business

If you ask a project manager if a project that is due to be completed at the end of next year is on track, they will very often say that if nothing goes too wrong, it is. Of course, he would need more people. This is despite the fact that he is convinced that the project is not on track or the whole project is pointless.

For a project manager, his norm is his monthly paycheck. If the entire project is useless or the team can’t deliver, 12 months of his livelihood is at risk. It’s better to be fired 12 months from now than right away, and if he knows up front that the project isn’t going to happen, no one even has to try that hard.

So it’s best for the team delivering the project when something goes very wrong at the very last minute and no one could have foreseen it.

For an entrepreneur or a company, this is of course the worst case scenario. It burns resources to deliver the project, the team doesn’t try, and the information that’s been on the team for a long time doesn’t get to the people who are paying for the project.

If not completing a project on time should cost a company money, the information that it won’t get done is worth some cost. Let’s take a simplified example – a customer wants a project delivered in 12 months. If the deadline is met, the company gets paid; if not, the invoiced amount is zero. Five people are to work on the project with an average cost of $3000 per month, which is a cost of $180,000 for the duration of the project. The price of the project that customer pays if it is delivered on time is $300,000. If we decide to sign such a contract, we have two options – a loss of 180k or a profit of 120k. If only we knew if the team can deliver…

Suppose a company has a hundred employees and creates a bet. The specific method of the wager may vary, but the “tickets” must be tradeable. For example, it can say “here’s ten thousand dollars, we’re going to bet on you not making it”. Anyone can put more money on any pile (bet on yes or no).

If the team believes they can make it, they can bet. Of course, the janitor can also bet, but the chances of them betting right are pretty slim. If anyone in the company has information, they can bet as well. For example, a key programmer got pregnant a week ago, but doesn’t want to tell her employer yet, but she won’t be productive in six months. Or on the other side – I like the project and want to participate and help make it on time. From the resulting price ratio, the entrepreneur can decide whether to go ahead with the project (if not, they can, for example, refund everyone’s money).

This type of gambling is not legal in all countries, so there is another way to do it – YES tickets are given for free to all employees and are tradable on the internal platform (for NO tickets if you are not allowed to trade for money). In either case, the company spends some money to get quality information. If the trading works even during the development of the project, the information is updated. In doing so, no one has to be the one to say “it’s not happening”. All they have to do is stop believing it and sell their YES tickets. The company can then address the situation immediately.

This principle is also used by companies. Google, Microsoft and HP run their internal prediction markets. Best Buy opened an internal prediction market to see if they could open a store in Shanghai by the required deadline – they found out they couldn’t and saved money by managing the situation.

For a while, the U.S. military used prediction markets to predict meeting deadlines to test weapon systems. Multiple teams were needed to properly test a complex system. If even one of them didn’t deliver their part on time, the test had to be canceled and rescheduled. Cancelling such a test was extremely expensive, so it was worth it for them to create a prediction market to learn this information.

Why don’t they continue? The prediction market was very accurate. And the military personnel were not exactly thrilled when it became clear a year ahead that they weren’t keeping up. It raises “stupid questions” like “who is incompetent and needs to be replaced?”. A better option is “it went wrong at the last minute and no one could have foreseen it”. After all, the taxpayer will just pay for it.

By the way, if we make decisions based on prediction market prices, they are called decision markets.

CEO Selection – Decision Markets

Corporate prediction markets may also be publicly traded. The stock market is the basic prediction market telling about the future performance of a publicly traded company. If I have information that a company could do better than the value of that firm’s stock says, it is worth buying the stock. Thus, stock price movements are a quick and efficient way of gathering information about which companies will do well. (Of course the obvious problem is central banks “saving the economy” and distorting prices by buying assets such as stocks).

But we use share prices to compare individual companies, how do we use them to improve a single company?

Suppose the head of a company retires and the board selects two possible successors. Who will be better?

A firm can create a new type of stock that is conditioned on the selection of a given CEO. Thus, “this share will be converted to a regular share if the CEO of the firm is Alice”. Suddenly we have two tradable shares. If I have information that Alice will lead the company into bankruptcy, I short/sell and buy the other stock instead. That way the CEO of the company gets picked by the market – whichever stock is worth more, that person will be CEO. (One still has to deal with what to do with the other shares whose condition has not been met, there are several ways to do that as well).

And here again come the insiders – but insiders to the decision in question. It could be a colleague of Alice from a previous company who knows both candidates and knows their capabilities. It may be someone who knows that Alice has a problem with gambling on prediction markets or microdosing heroin. It may be Alice’s colleagues at the firm who know that Alice is a good leader and gets along with others, and if she is their boss, they will help her increase the profits of the company. It doesn’t matter if the insider is from inside or outside the company, the point is that only a person who sees the wrong market price can be predictably successful in the long run. That is, they know something that the market has not yet detected.

Anonymity and ethics of insider trading

Anonymity, for example using Chaumian tokens (no, you don’t need a blockchain for that) is important in this case. Alice can bet on her competitor if she knows he will be a better CEO. The project manager can bet on “we won’t make it” and still pretend that everything is going according to the plan. A competitor who knows his company is in trouble can buy the stock of a competitor who will win – for example, the CTO of a cell phone carrier knows they made a bad decision and invested in a technology that will crumble under their hands can buy the competitor’s stock (or buy options, either puts on their company or calls on the competitor). This is a positive feature of prediction markets, and if they are anonymous, they deliver better information.

Similarly, insider trading is highly regulated in most countries, and there is a fundamental misunderstanding of the market and its purpose. A trader in the prediction market makes money if he has information that is not publicly available (and therefore not yet included in the price). Only then can they move the price correctly, and only then does the price contain relevant information. In both prediction markets (including equities as a special case of prediction markets) and decision markets, it is the insider information that we want. The insider’s “disproportionate profit” is actually a good deal for the society – someone sells us information and makes money on it. A well set up prediction market will ensure that the information we buy has a higher value – that is, for example, we make a much better decision than the price we pay for the information. And a well-functioning prediction market attracts and supports insiders who have the best information. At the same time, the presence of money and market prices provides skin in the game. It’s not “opinion over coffee” or the opinion of an analyst in the media.

Futarchy

The concept of prediction markets was developed by Professor Robin Hanson, who was also a guest in Bratislava or at the Hackers Congress Parallel Polis 2019. He is the originator of the Futarchy concept, whereby a government can define targets (e.g. employment, GDP growth, etc.) and a set of decision markets, based on market prices, will determine the path that gets us there. Will immigrants take our jobs? Both the anti-immigration alt-right and all-inclusive progressives will never end this “social debate”. They are separate groups who even pride themselves on not listening to each other (“You don’t discuss with Nazis”, “Progressives are paid by Soros, if I want to know what Soros thinks, I’ll ask him”).

If we ask people for their opinion, we usually learn the result of the emergent phenomenon of social bubbles. A student of Cambridge and a businessman in New York will have a different opinion. But whose opinion is worth more? In a democracy, it is those who have more votes (at least indirectly). It’s just that not everyone’s opinion has equal weight on this issue.

The question of immigration is a difference in values and it is hard to choose which values are better. But if we are asking about which values lead to better measurable results, we only want to know the opinion of insiders who have sufficient information.

Thus we want speculators with skin in the game. We want insiders and speculation, not protection from insiders and speculators!

How to try it

We don’t need to bet on the outcome of the US presidential election or use sophisticated crypto markets to understand the functionality of prediction markets. If you have a good murder mystery movie, you can create a prediction market and trade while watching the movie. Robin Hanson has written a tutorial on how to create such a game.

I’ll be glad if you can advise me on good movies that I haven’t seen yet.

What if experts are not rich?

Risk perception and handling of risk matters. Someone may think Trump will win, but they’d rather sell a ticket for 5 cent profit now than win a dollar later. Maybe they are not confident enough, maybe they do not like risk. In his wonderful blog about prediction markets, Vitalik Buterin explained that after the election results were announced and judges refused Trump’s appeal, the nTrump (NO) ticket still traded for 85 cents on a dollar. Vitalik put up 1 million dollars worth of ether as collateral to borrow around $300k in DAI in order to win a little bit more than $50k. He saw it as a no-brainer, but most people don’t want to bet that kind of money even on obvious results.

The difference between people who are (just) experts and entrepreneurs is largely in the perception of risk. Therefore, entrepreneurs, i.e., traders of information in the prediction market in this case, are tasked with obtaining information from other insiders or experts and evaluating who among them is right.

To take an example from the beginning – the person who made the bet against Trump winning had some information before it was common knowledge (common knowledge is already included by the market in the market price). It could have been, for example, someone who had a sufficient amount of YES tokens which they exchanged for NO tokens at good odds. For example, his buddy is a temp who counts votes in Michigan. So the trader is gathering information, evaluating its relevance and importance to the future price.

Let’s try another example – I want to invest in a company that makes a vaccine for COVID-19. If all the firms are publicly traded, this can be done through stocks, but if it’s a huge pharmaceutical company whose price is affected by a number of other factors, I could have done it with a bet on the first approved vaccine for general use.

To make it a good deal, of course, I need to know who is how close, whether anyone has failed, what types of vaccines even have a chance of working, etc. I can ask immunologists, doctors, and experts who might not want to bet – and for good information offer them money. For example I can offer them upside, but reduce their downside or upfront investment need. That means I can use expert opinion while avoiding the risk. Of course, I have to evaluate which of the experts I asked are right and which prices are wrong in the market myself.

With experts, a plurality of opinions, domain knowledge, and analysis of options are required. But skin-in-the-game traders have to choose who is right. That’s the only way to consistently make money in the market. As a side effect of their earnings, we have timely and quality information. This does change over time, but there is only ever one market price at any given time thanks to arbitrageurs.

The cobra effect and how to change the world with prediction markets

“The British government in India was concerned about the number of poisonous cobras in Delhi. It therefore offered bounties for every dead cobra. Initially, it was a successful strategy where a large number of snakes were killed for the bounty. Later, however, enterprising people started breeding cobras so that they could then get paid for killing them. When the true situation was discovered, the government stopped the project and the cobra breeders released the venomous snakes into the wild. The population of wild cobras even increased. A seemingly effective solution to the problem has made the situation even worse.”

Based on this anecdote, the unintended consequences effect is named the cobra effect – an attempt to solve a problem will make the problem worse. Imagine if, when asked if they were struggling to deliver a project on time, someone other than the company itself got a large investment on the NO side. Then someone would infect the team with flu. The power would start going out while compiling code at night. The main programmer suddenly starting to go to parties every night, his productivity would drop. He was attracted to the parties by a femme fatale, working for the “NO” investor. With prediction markets, it’s important to realize that the very existence of the market and its setup can affect the outcome.

Normally this is a positive. If the whole team is invested in YES, because you can’t invest in NO, they can try harder. This, by the way, is why some companies give employees stock options or profit share. This way employees can directly influence the value of the company and make money. But they don’t directly have shares – the options expire, so the benefit only works if the employees are still with the company (in any given year).

The prediction market can thus both collect information and serve as a bonus scheme. Each employee can choose whether they want a higher bonus when the target is met or whether they prefer to receive some money right away. This will suit people with different risk appetites.

In this way, prediction markets can also be used to crowdsource non-numerical information. For example, Parallel Polis posted a link to an anonymous prediction market for the publication date of Andrej Danko’s final thesis, which was supposed to be plagiarism. Of course, anyone can express an opinion in it. But whoever has access to the thesis (i.e. insider info) can arrange for the thesis to be published anonymously by a specified date and then collect the prize – in an anonymous cryptocurrency.

This actually makes the people who are betting on it not being released in public by a given date crowdfund the disclosure. And they only pay for it if the disclosure happens. Those who have access to the work are incentivized to win the money collected. And they don’t have to reveal their identity directly – they don’t even have to have access to the information, they just have to “secure” the leak.

Prediction markets can thus motivate people to act. Just beware of the cobra effect. By the way, from this one can estimate the approximate value of the electoral vote. How many votes does it take to influence the outcome so that I’m sure to make money? And watch out, the other side can do it too.

Bounty programmes work on a similar principle. My project Hacktrophy allows ethical hackers to search for security vulnerabilities and, if they are successful, get a reward for finding the vulnerability. Even my own website is in this program. A bounty program also motivated the first transatlantic flight (Orteig prize), the first reusable aircraft to cross the 100km “space” boundary twice in a row within two weeks (X-Prize), and a number of other cool things. Financial motivation to solve global as well as local problems is quite common nowadays. Netflix, for example, paid out a million dollars to a team that improved their prediction algorithm.

So when it is good to use a prediction or decision market and when to pay out bounties directly? If anonymity, insider information, or multi-entity collaboration is needed, the prediction market is better. Also, if we want to give the market the option to decide not to pay out – for example, Andrej Danko could bet that his rigorous will not leak, thus reducing the incentive to leak (he would get part of the bounty). And those who wanted it to leak would get the money. And of course, the prediction market is better when the market prices themselves give us useful information before the event comes to be evaluated.

What kinds of prediction markets are there?

A proper prediction market must satisfy three properties:

- It uses real money

- It is easy to use

- It is easy to create a new market with a question

All three of these features also allude to regulations. Some markets (like Metaculus, Manifold and Foretold) don’t use real money, just some points. This makes them more of a signaling tool than a real betting tool, where the market participants have skin in the game. The reason for this is often just regulation – betting with real money is considered gambling by many states and thus either banned outright or with a lot of red tape and there are many stamps required.

Fortunately, we have crypto markets that “live” in a cloud outside of standard jurisdictions. For example, decentralized Augur (not exactly easy to use) is one such market. Some markets such as Polymarket, in turn, do not meet the condition of simply creating a new market with a question. Other interesting options are InsightPrediction, ExoticMarkets.xyz or Omen.

Conclusion

Prediction markets are not roulette. The market price provides useful information on which we can make better decisions. It’s a way to crowdsource the knowledge of the people who go to market with skin in the game. They are not the domain of pure crypto markets and betting companies, but are also used internally by companies to crowdsource information.

A nice use would be to figure out, for example, how to reduce COVID-19 casualties the most with the least economic impact. We should not just listen to ‘our’ experts, but get information from the best experts and knowledge investors from around the world. If, for example, a billionaire has a really good plan, backed by experts, I believe they would invest in the best solution in order to win the bet. And we would consider social media discussions or a politician’s press conference for what they truly are – cheap entertainment.

This blog is a chapter from my book:

Find more content like this in my book Cryptocurrencies – Hack your way to a better life.

It is a guide for Bitcoin and cryptocurrency ninjas. Learn how to use the Lightning network, how to accept cryptocurrencies, what opportunities there are for different professions, how to handle different market situations and how to use crypto to improve your life.

Get it on my e-shop (BTC, BTC⚡️ and XMR and even oldschool plastic) or at Amazon.