I’ve recently had conversations with several people about non-ionizing radiation (such as WiFi, mobile networks, and similar technologies). I was amused to discover that people have completely distorted ideas—off by several orders of magnitude—about what emits radiation and how. That’s why I decided to build a simulation.

The common thinking goes like this: “I don’t want a WiFi router in my bedroom—I don’t want it blasting me.” And then they plug their phone into the charger with mobile data still on. The irony is that placing your WiFi router closer to you (and your devices) actually reduces the radiated power (when counted as exposure to your body). And WiFi as a whole is practically negligible compared to mobile networks. So I created a simulation where you can explore different scenarios. Play around with it—instructions below.

A dive into the void

In the 1960s, physicist Richard Feynman’s insatiable curiosity led him to the laboratory of John C. Lilly—the neurologist who invented the sensory deprivation tank, also known as a floating tank. It was a completely dark, soundproof pod (shaped like an “egg”) filled with salt water heated to body temperature, designed to dissolve the boundary between body and emptiness. Feynman, always eager to explore “hallucinations” without “messing with his brain” through drugs, was ready to take the plunge.

But just as he was about to step in, he was stopped by a rhythmic mechanical hissing: air pumps.

Feynman asked what the noise was. Lilly explained that the pumps were essential for supplying fresh oxygen. For most people, the enclosed, coffin-like chamber triggers a fear of suffocation. Standing there in his swim trunks, Feynman did a quick mental calculation: he compared the air volume inside the tank to the metabolic oxygen consumption of a resting human. Then he looked at Lilly and told him the pumps were completely unnecessary—a person could stay sealed inside for hours before they’d start to suffocate. As Feynman later described in his book Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman!:

“I said, ‘I calculated that there’s enough air in here for eight hours… why the hell don’t you turn that thing off?'”

Lilly probably knew the physics, but he kept the pumps running to soothe the “normal” fears of other people. He just smiled and agreed. He hit the switch, absolute silence fell, and Feynman floated in the darkness. It was a classic “Feynman moment”: while others were driven by instinctive fear, he was guided by the quiet, unwavering certainty of the laws of physics.

This story is the inspiration for this blog post. We see the little antennas on WiFi routers and the massive antennas of cell towers on rooftops, and we immediately feel like we’re being bombarded with dangerous radiation. Let’s take a look at the physics—you might be surprised to learn that a far worse source of radiation is the phone you carry in your pocket or hold in your hand all day.

Transmitting vs. receiving

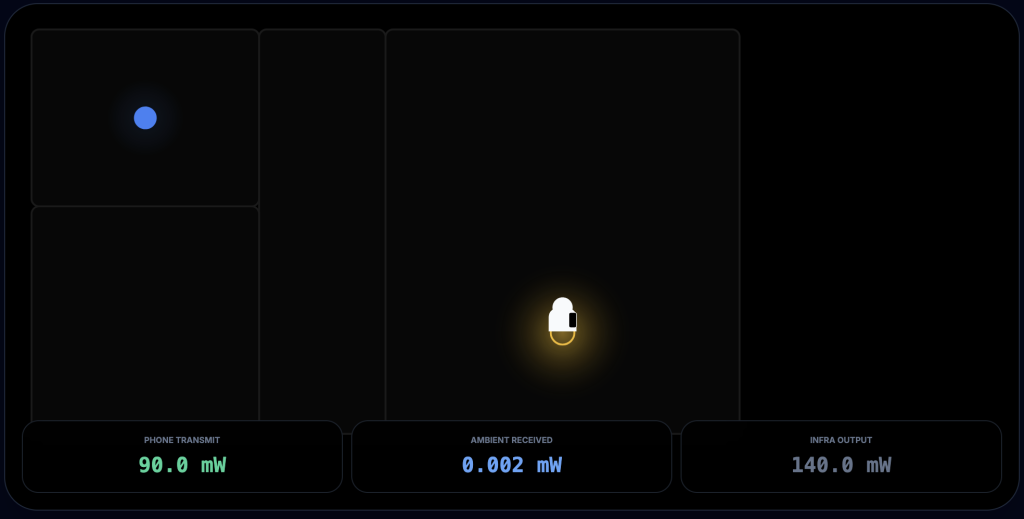

Image: Your device transmits at 90 mW when you’re in a different room—much more than the radiation intensity reaching you from the WiFi router.

The biggest source of non-ionizing radiation from both WiFi and mobile networks is almost always your own device. Even when you’re doing something passive (like watching a video), your device is transmitting (sending acknowledgments, requesting the next video segment, etc.). During calls (especially video calls), it transmits even more.

The intensity of this radiation is inversely proportional to the square of the distance. So if your phone is one centimetre from your ear, you’re getting a hefty dose. Increase the distance tenfold (to ten centimetres), and you get one hundredth (ten squared) of the radiation. Put the device a metre away, and you get ten thousand times less exposure than when it’s pressed to your ear.

If your WiFi transmitter is in the same room, it’s probably farther from you than the device you’re actually using. This means the vast majority of non-ionizing radiation comes from your own device, not from the WiFi router.

Power adjustment

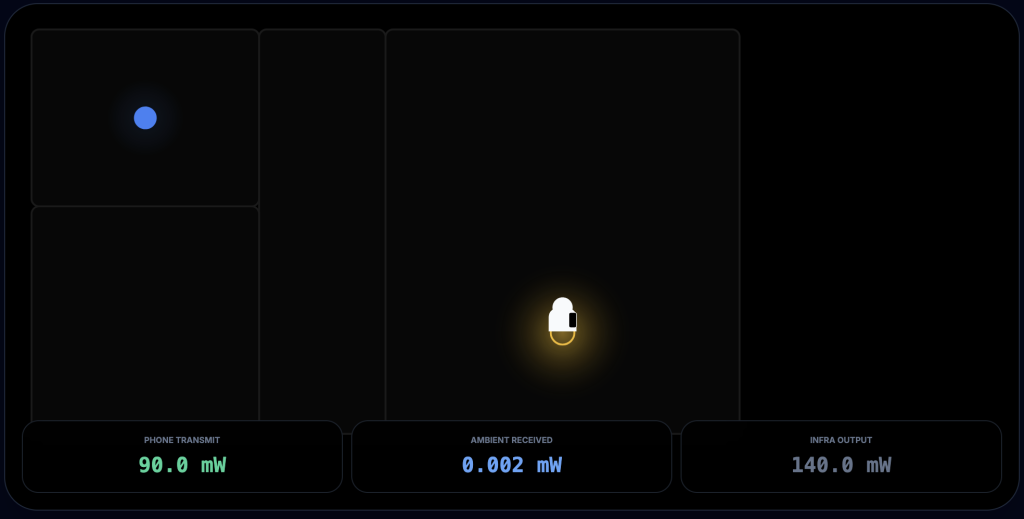

Your devices (unless they’re ancient) adjust their transmission power based on need. This applies to both WiFi and mobile networks, and it works on both ends—the access point and your device. This means that if your WiFi router is in the same room as you (so the signal doesn’t have to pass through a wall), both devices transmit much less.

Image: The user moved into the same room as the WiFi router. Radiation from the router increased slightly, but transmission from your device dropped dramatically.

Paradoxically, this also applies to mobile networks—the closer you are to the cell tower, the less your device needs to transmit. And your device’s transmission exposes you to far more radiation than that big scary antenna on the rooftop.

WiFi access points in a mesh network

Image: The device is “blasting” because the signal has to pass through a wall.

If you want to minimize your radiation exposure while carrying a mobile phone or sitting at a WiFi-connected computer, it’s best to have a WiFi access point close to you. That “scary” box with antennas will actually reduce your exposure.

Image: Thanks to the mesh network, total exposure is much lower because our device transmits much less. Ambient exposure (for someone not carrying a transmitter) increases slightly because the access points communicate with each other over WiFi.

Since WiFi access points are also connected to each other via radio, environmental radiation is slightly higher—but still negligible. This can be solved by connecting the access points with Ethernet cables.

Image: Access points are connected via cable.

If you want wireless connectivity for your devices, this is probably the best practical scenario today. At least until the already-existing LiFi technology becomes widespread—which uses light instead of radio waves for connectivity.

WiFi vs. mobile signal

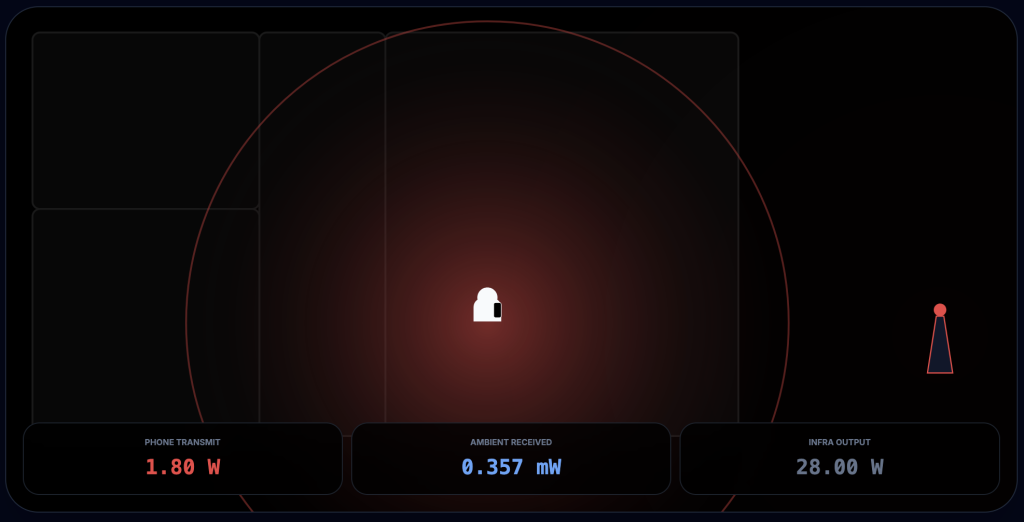

In practice, your phone transmits at 20 to 100 times higher power on mobile networks than on WiFi.

If you’re trying to protect yourself from radiation by avoiding WiFi and using mobile networks instead, you’re actually getting the highest dose of radiation. And the farther you are from the cell tower, the worse it gets.

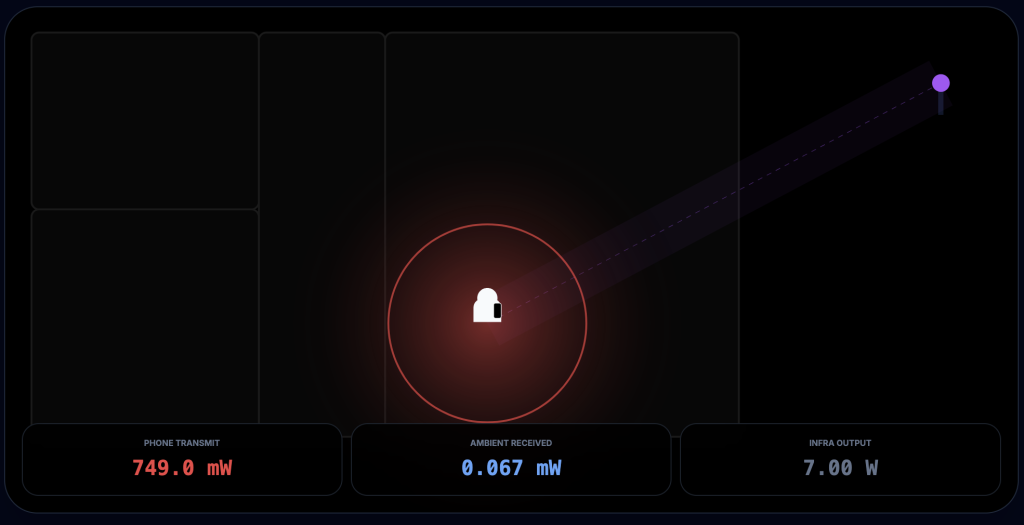

Image: Your phone has to “blast” 20–100 times harder to reach through your home’s walls.

Interestingly, 5G networks can use mmWave technology. People are frightened by this because access points are placed just a few hundred metres apart. But the practical result is a significant reduction in transmission power. Additionally, they use beamforming technology, which directs the station’s transmission straight at the mobile device instead of broadcasting across the entire sector.

It’s similar technology to what Starlink uses, which is how it can cover vast areas without causing radio interference over a wide region. It’s a bit like a “laser” but with radio waves.

Image: Beamforming technology in 5G mmWave.

Thanks to this, it’s possible to use low transmission power while sending signals directly to devices.

It’s important to note that mmWave technology isn’t widely deployed—it’s mainly used in places with extremely high concentrations of people.

What I didn’t say, and what you should do

I can’t tell you whether non-ionizing radiation is actually a problem—there are endless debates about it, and I haven’t formed an opinion. It certainly has some effect, at least thermal, and although not universally accepted, there’s also a potential effect on so-called Voltage-Gated Calcium Channels (VGCCs). This blog post is for people who care about non-ionizing radiation, but we won’t be examining whether it’s actually a problem.

People often make mistakes by reducing the number of access points out of fear of this radiation, or by using only mobile networks instead of WiFi. This blog assumes that radiation is a concern and explores how to reduce it without drastically compromising quality of life.

Of course, if you really care deeply about this radiation, you should use wired-only devices and avoid both WiFi and mobile networks entirely.

But if that would limit your quality of life (as it would for most people), I recommend keeping your phone in airplane mode with WiFi enabled (this disables the mobile signal—turning off mobile data alone isn’t enough). If you still want to be reachable by phone, you can use VoIP and forward calls to a VoIP number when you’re unavailable. That way, people can reach you over WiFi. Some carriers also support WiFi calling directly. And of course, the best option is to skip carrier calls entirely and use encrypted apps like Signal (or WhatsApp if nothing else works). In Latin America, for example, WhatsApp is used almost exclusively for communication. These calls work over whatever data connection is available.

Critics of 5G mmWave technology argue that the bandwidth and transfer speeds are so high that much stronger radiation occurs simply due to the sheer amount of data transmitted. There’s something to this, although the question is whether you wouldn’t transmit the same data anyway—just more slowly. That’s not always the case, though—for example, video calls often reduce quality (and therefore data volume) on slower connections. And beyond that, a “regime change” can’t be ruled out: beyond a certain level of radiation, qualitatively different things might happen in the body.

Probably the worst solution is turning off WiFi at night while leaving mobile data on (“just in case something happens”). If you leave WiFi on, your total exposure will be lower. Besides, mobile devices often update overnight, which means data transfers are happening.

A good option is to leave your phone on, keep WiFi enabled, and optionally disable mobile data. But even with mobile data on, it’s better to also leave WiFi enabled, because mobile devices prefer data transfers over WiFi, and your total exposure will be lower.

Take the specific numbers in the simulation with a grain of salt. For example, the app shows maximum mobile network power as 1.8 W, but most phones don’t transmit more than 400 mW. What matters are the orders of magnitude—the 20–100x higher power for mobile networks vs. WiFi holds true. And the physical law stating that effective radiation decreases with the square of the distance definitely holds true. These are truly order-of-magnitude differences. Whether a device transmits 1 mW or 5 mW isn’t as significant as the difference between 1 mW and 200 mW.

The app

You can play around with the app that generated these images here. It describes various scenarios—you can choose between a video call (lots of transmission) vs. downloading (streaming) video, and different connection setups. By clicking, you can move the user between rooms or place them outside.