I was prompted to write this article when the X (Twitter) app stopped working on my phone. The culprit? New technologies that are fundamentally restricting what users can do with their own devices.

A Brief History Lesson

The internet was born as an open platform, built on protocols that anyone could implement. TCP/IP, HTTP, TLS, SMTP, POP3, IMAP, FTP – these protocols meant you could use any compatible software, and your apps and operating system would just work. The opposite of this were closed communication platforms or operating systems with native apps (good luck running an .exe file on Linux or Mac – though Linux apps usually came with source code, so you could compile them anywhere).

We largely solved this problem. As Mac usage grew (along with Linux to some extent) and mobile platforms emerged, several positive changes took hold:

- Frameworks and programming languages (Java, JavaScript) enabled cross-platform applications. The dream was simple: write one app in Java, run it everywhere. Java may have lost some of its cool factor, but frameworks delivering similar capabilities have exploded, making quality cross-platform development a reality today.

- Protocols versus platforms. We’re replaying this battle right now and the pendulum is swinging back, but it’s important to understand what happened. The Web 2.0 revolution and browser wars gave us websites and web apps that ran on any platform with a browser. It was the marriage of protocols and standard technologies that let you use sophisticated apps (like Google Docs, which dethroned the then-dominant Microsoft Office). For email, it didn’t matter whether you used Hotmail, Gmail, or Protonmail. Calendar invites work as email attachments regardless of which calendar app you prefer. You can send Bitcoin no matter which wallet you or your recipient uses. All of this is possible thanks to open protocols.

- Open-source and free software meant that even if the original developer didn’t have access to a particular operating system or device, someone else could port the app. The open-source model completely disrupted software sales, though we somewhat unfortunately pivoted to another model – Software as a Service (SaaS). People now pay monthly subscriptions for every app imaginable. But open source was a massive force, adopted even by its former arch-enemies. Microsoft bought GitHub, where most development happens, and now releases enormous amounts of open-source software. Their primary interest is getting you to pay for subscriptions to their software or infrastructure. If open source helps customers accomplish more, they’re happy about it.

All three of these models are now under threat. Software developers often proudly announce their app is “Mac only” – the buttons are curved and painted exactly as the designers of some non-portable framework intended. Platforms are winning over protocols. We’ve stopped using protocols like XMPP and SMTP, switching to Facebook, Twitter/X, and others. These platforms severely restrict which software you can use to access them, which in turn diminishes the advantages of open source. And the open-source model itself is being undermined by new gatekeepers – app stores that are bringing back the old software sales model while taking their cut.

But there’s a bigger problem that many people don’t see yet – one that’s just arriving and represents a powerful negative force.

Goodbye APIs – Platforms Win Over Protocols

Our devices mostly contain processors capable of running any code. Feed them a video game, a web browser, or an operating system, and they’ll execute it. If you’re running a program that communicates via an open protocol (a web browser, podcast player, email client, etc.), it doesn’t really matter what the code looks like – if you want, you can use open-source alternatives and they’ll work just as well. If you want to change anything about how that client works, you can.

Many platforms used to work similarly. Both Facebook and Twitter had web interfaces and mobile apps, but if you wanted to use an alternative client, you could. This spawned various apps like Buffer, Hootsuite, and TweetDeck that let you interact with content differently. The first restrictions came after the Cambridge Analytica scandal, when these APIs were exploited to profile people for targeted political marketing (which, incidentally, appears to have been massively overhyped in terms of actual impact). Many API calls, and thus the apps that relied on them, were restricted.

After Elon Musk and friends bought Twitter, this platform also severely limited API access. Open clients using the protocol are no longer allowed – you have to pay for API access, and even that API is restricted. Jack Dorsey, Twitter’s founder, has said that making Twitter a platform and app rather than a protocol was its biggest mistake. That’s why he started supporting the BlueSky project while still at Twitter, and now backs the open Nostr protocol, which solves this problem.

Of course, since apps are built on open web technologies, it was still possible to analyze how the official app (or website) communicates with the server and replicate that behavior. So platforms developed various methods to detect whether someone is using a modified app.

A beautiful example of how this works is Pavel Trávník’s bubbles project. The idea is simple: let’s share our lists of blocked people on Facebook. If a good friend of mine blocked someone, it’s probably a good idea for me to block them too. Since social networks are all about attention, giving attention to negative people doesn’t pay off. And sometimes bad behavior deserves social ostracism as punishment. A project like this saves time. The automated blocking works through a web browser controlled by an automation tool. This typically fails already at the password entry stage, when JavaScript on the page detects that nobody is actually typing on a keyboard, or the typing rhythm is too regular. And if you try to import a list of a hundred blocked people, the server notices you’re blocking way too fast for manual operation and blocks you instead.

All these blocking methods, however, depend on heuristics – it’s a cat-and-mouse game. You can type the password slowly, or the app can prompt you to log in manually. There can be random, fairly long delays between individual blocks to avoid looking suspicious – if the app runs in the background for two days, who cares?

Hardware Attestation

And here we arrive at a technology that most of you carry in your pocket without even knowing it. You have “your” phone, sure, but it’s no longer a general-purpose processor that will run whatever code you tell it to. And even if it is (like a Pixel phone with GrapheneOS), apps can request hardware attestation that you can’t bypass even with open-source software.

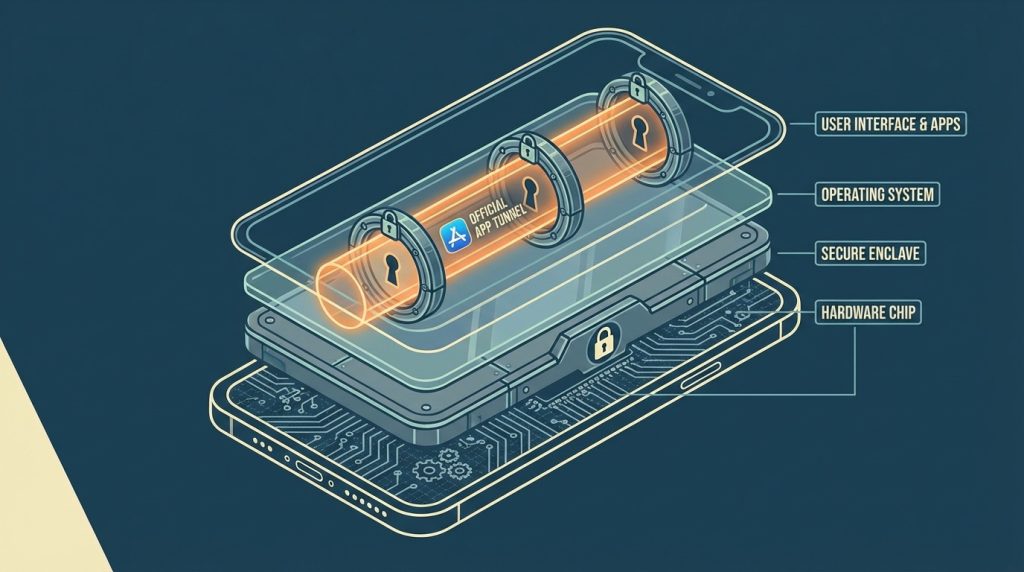

The processor in your device knows which operating system is running. It can verify keys from the bootloader all the way to the OS. It also knows which app is running (and its hash) and where it was installed from. It can even guarantee that an application is isolated and no other apps are interfering with its operation. All of this is guaranteed by the processor – regardless of which operating system you have installed. The processor has a signing key that was generated in the factory and is unique to your device.

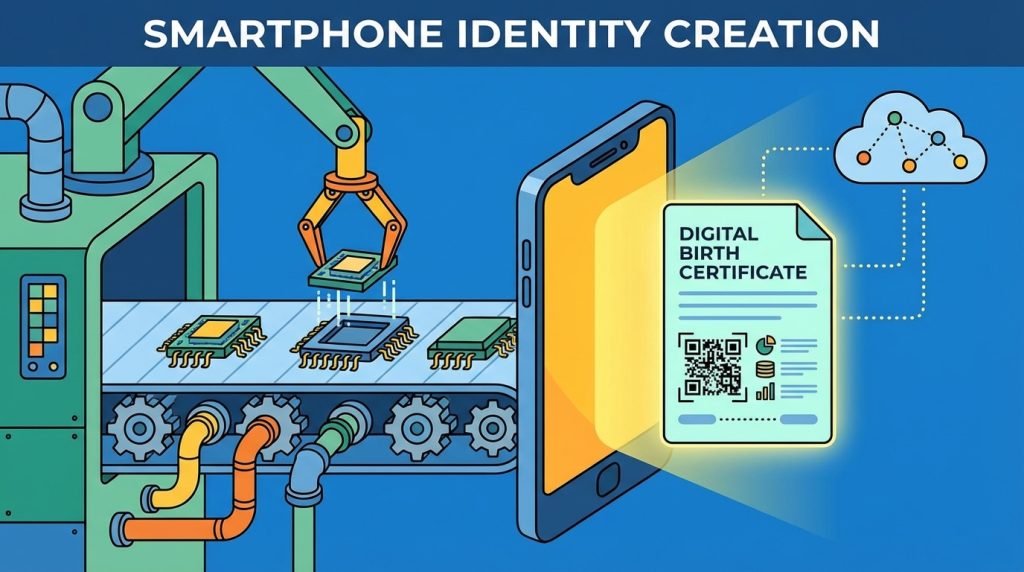

The Processor’s Birth Certificate

The processor’s key isn’t just stored in memory where it could be copied. It’s created at the chip’s “birth” in the factory, often burned into silicon or derived from microscopic manufacturing imperfections called PUF (Physically Unclonable Function). These imperfections are as unique as a human fingerprint and serve to generate a key that nobody – not even the manufacturer – knows or can copy. They can only cryptographically sign it at the factory.

The result is that a freshly manufactured chip has a private key inside it. When activated, it simply announces “my corresponding public key is this number,” and the factory system signs that public key (“processor manufactured according to standards”). The processor has hardware restrictions on when and how it will sign things with that key.

These technologies are known as Secure Enclave in Apple’s world, TrustZone (ARM technology used in Android devices), or TPM and SGX in computers and servers. It’s essentially a separate, miniature computer within the computer, with its own memory and logic, invisible to the operating system – and even to you with full administrator rights.

This is where mechanisms like Google’s Play Integrity API or Apple’s App Attest come in, using this hardware vault as a notary. When you launch a banking app or a game, it asks the vault to issue a “certificate of authenticity.” The vault checks whether the system has been altered, whether it’s running on an emulator at some server farm in China, and digitally signs this report with that non-extractable key, while the server on the other end verifies the manufacturer’s signature. App developers now have a powerful weapon that gives them near-mathematical certainty that they’re dealing with a real, unmodified physical device, not some script trying to hack the game or create thousands of fake accounts. For developers, this means the end of cheap spam and a fair playing field for gamers. But for us, it means that if we don’t have a “kosher” system approved by the manufacturer, the door to the service stays closed.

This technology reaches even further, enabling something that sounds paradoxical – secure data processing on someone else’s hardware without the hardware owner seeing it. A prime example is Signal’s contact discovery solution. Signal needs to figure out which of your contacts use their app, but for privacy reasons, they can’t see your contact list in readable form. So they send your encrypted phone numbers to a special enclave on their servers (built on Intel SGX technology). This enclave decrypts the data in isolation, performs the comparison, and returns the result – while Signal’s operators and any potential hackers on their servers never see your contacts, because they don’t have the key to the running enclave. It shows that hardware attestation can serve privacy protection, even though its primary deployment in the mobile world tends toward tightening control over what you’re allowed to do with your device.

This technology can be used for various other good purposes. Some cryptocurrency bridges between networks use it, and it can even enable private smart contracts whose correct execution is certified by the processor key in the secure enclave, but it is invisible to the decentralized network participants.

Why X and Many Other Apps Don’t Work for Me

App developers have been waiting for these technologies to reach critical mass. The X app (formerly Twitter), for instance, now refuses to log you in unless full attestation passes. This means the only people who can sign in through the app are those with a certified, non-rooted phone, running the manufacturer’s original operating system, using the original unmodified X app installed from the Play Store or App Store. Attestation might even fail if your operating system is too old and might have security vulnerabilities.

For developers, it’s a way to ensure users have a reasonably secure environment, that they’re actually talking to the official app and not some script or bot. It enables spam prevention, account creation restrictions, and blocking ad blockers.

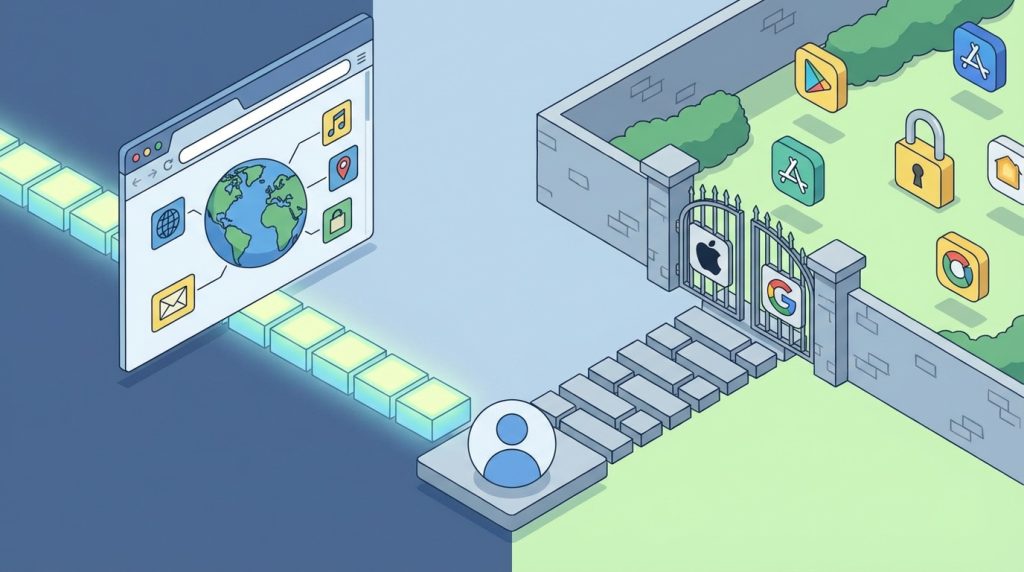

But it also runs completely counter to the internet’s philosophy. Instead of protocols that internet services were built on, we now have end-to-end controlled apps where we don’t even control the part running on our own device – our own property. If we decide to install a different operating system, or exercise our right to modify it under open-source licenses, we’re out of luck.

What’s even sadder is that we’re now locked into two companies – Google and Apple – and their approved partners. GrapheneOS, for example, is a much more secure Android than stock Android, with numerous security patches. There’s a way to verify that official, non-rooted GrapheneOS is running using hardware attestation, but since it’s not signed with Google’s key, most app developers don’t support it (but it is possible!). This is somewhat paradoxical – all the guarantees that attestation provides are actually stronger on GrapheneOS than on official Androids: no rooting or app tampering, the absolute latest security updates that often reach official manufacturer firmware weeks or months later.

Users of Huawei phones face similar problems. While based on Android, Huawei is no longer friends with Google, so attestation fails.

What’s in It for Google and Apple?

Despite Google’s ecosystem being relatively open and Android itself being open-source, its usefulness drops significantly without the Android license that most manufacturers pay for. Google has provided a technology that ensures most users will have to stay within the Google ecosystem, including their app store, from which they take a cut of every sale.

Paradoxically, they achieved this by offering app developers a useful service while simultaneously devaluing products from (cheaper or better) competitors who might want to build on open Android technologies without paying Google’s fees. Home tinkerers and small companies won’t be able to create devices that are nearly as usable.

What’s even worse, attestation also verifies whether the operating system is up-to-date and secure. If you buy a cheaper device with short-term security update support, you could easily find yourself in a situation where, a year or two after the last update, even apps that used to work – X, banking apps, and the like – simply stop functioning. Your only option is to buy a new device. Since you’re locked into the Google ecosystem, probably because you’ve purchased some apps through the Play Store, it’ll be another device with Google’s stamp of approval (even if from an alternative manufacturer). So you won’t switch to Huawei or Apple. On Huawei, apps won’t work because of attestation, and on Apple’s platform, you’d have to repurchase many of your apps.

This pressure isn’t fully here yet – not all apps (with X being a notable exception) require hardcore attestation. But eventually, you’ll be forced to upgrade your hardware simply because it will become unusable. And despite Android’s core being open-source, you can’t even update it with help from the community. Alternative operating systems like LineageOS, which used to give older devices a longer life, won’t be a solution anymore. Sure, you can have a more secure system with updates on your device, but attestation will fail anyway.

The Solution

For X and many other apps, the solution is to return to the internet’s original philosophy – using open protocols instead of apps. This still works, for now. You can use X in a browser, and it can even behave somewhat like an app through “Add to Homescreen.” This technology is called Progressive Web App.

Since people still access X and other services from desktop computers, we’ll have web access as long as a similar attestation system isn’t available on most desktop operating systems. But this isn’t always a solution – some banks have no web interface at all, or require an app with attestation just to log into the web interface.

Specifically for X, you can even use a browser extension called Control Panel for Twitter, which lets you modify X’s behavior in your browser – blocking certain features, adding others, hiding ads, and so on. So exactly what they tried to prevent with attestation still works in the browser. And paradoxically, the more of us who use the web version, the less likely it is to disappear entirely – if enough people use X through the web and refuse to use the app, the attestation game won’t work.

However, many paid services simply don’t care about GrapheneOS users or phones from other manufacturers. A bank can easily decide that if you’re using an Indian or Chinese phone without a Google birth certificate, you’re not an interesting customer. You can’t even afford a “proper phone.” And you’re excluded from modern services.

We’re partially losing the battle for an open internet, but the open internet in the form of web technologies is our strongest weapon. As long as users accessing apps via the web remain sufficiently valuable, we should at least preserve this option.

Conclusion

We fought a hard battle for an open internet (against closed platforms like AOL, Prodigy, and others). Free and open-source software won decisively – Linux is the most widespread operating system, running on routers, all Android devices, countless servers, and more. Free and open-source software gives users back the power to make their computing environment work the way they want.

Unfortunately, we somewhat missed the next battle and allowed two companies to completely dominate the app market. Whether an app makes it into Google Play or Apple’s App Store determines its survival. The same goes for mobile devices. I have a Daylight Computer and a Pixel with GrapheneOS, but whether apps will run on them is largely decided by Google. At least with GrapheneOS, app developers can choose to trust GrapheneOS keys too – which is a good idea that costs them nothing and actually gains them something.

We have an open internet, many open protocols, and even open source code. But we can’t use any of it. Through the open internet, only official apps can connect to services – not just anyone who can speak the protocol. And any modification to the operating system or app code, which licenses often explicitly permit, means the processor refuses to sign the attestation, and the app stops working entirely.